Part 3: Public Tile Services

Nowadays there are really two options for making an interactive web map: use somebody’s pre-fab tiles, or make and serve your own. Self-publishing used to be tricky business, but improving tile-rendering software and hosting services are making it easier. This process will be addressed in Section 5. Most mash-ups are still done atop big public tile sets, however, so it’s worth it to try and catalog the ones that are currently out there. If there’s an up-to-date list of tile services already out there, I haven’t found it. The closest thing is a woefully incomplete page on Wikipedia.6 This is understandable, as it is hard to keep up with the fast pace of development and change in these services.

The advantage of going the public tile service route is that there is a lot of good stuff already out there that can be accessed with a small amount of script. The list below is all of the public tile services covering the U.S that I have found. Many draw their data from the same sources but style them differently (Navteq and OpenStreetMap are the two most common data suppliers for the U.S., while there are other suppliers that cover other parts of the globe). Some (e.g. Google and ESRI) are cached, meaning the servers store a collection of static raster images which are sent in response to a client request, while others draw each tile from database data on demand. The descriptions below represent my own opinions on the cartography and functionality involved in each service at the time of this writing (June, 2012).

1. Google Maps: by far the most popular, Google changed the game when it published its API shortly after coming online back in 2005. Most folks with an internet connection faster than dialup are pretty familiar with the layout, zoom tools, base map controls, etc. Certainly, Street View is a nice feature (if you’ve never seen one in person, Google literally hires people to drive around in Priuses with funky-looking 360-degree cameras mounted to the top all over the world to get their photos). There are three base maps to choose from: street map, imagery (with or without a labels layer), and terrain, which is a nice combo of shaded relief and contours. Google’s API has a lot of functionality and styling options, and the new Fusion Tables service makes it a lot easier to render data dynamically, although it still has strict limits on how much data. It’s pretty easy to just drop an image or a bunch of point features on top of the map, and you can include the draw tools from My Places for users to add vectors on top.

(Incidentally, Google Maps seems to be the only service that can be easily embedded into a WordPress blog)

2. Bing Maps: A couple years back, Microsoft decided that their corporate moniker had too much mental association with pure evil, so when they overhauled their search engine to try and compete with Google, they onomatopoeiacally renamed it. Its slick look and feel gave Google a run for their money in the aesthetic realm. The tweening zoom makes Google feel jarring in comparison, and Bing was the first to implement angled “Bird’s Eye” aerial photography. The road map includes shaded relief at smaller scales, but there’s no close-in terrain feature. Google has yet to learn about shift-zoom (which was pioneered by OpenStreetMap—see below), but Bing has it down. They have published APIs forAJAX (JavaScript), Silverlight, iOS, and WPF (for developing desktop applications).

Bing’s Road basemap and interface

3. OpenStreetMap: The U.K. government’s Ordinance Survey guards its geographic data with utmost jealousy. This led a frustrated computer scientist name Steve Coast to found OpenStreetMap in 2004 as a bypass relying on volunteers to go map their cities with GPS units, creating one of the first crowdsourced mapping applications on the web.7 OSM now has over 600,000 registered users and about 20,000 contributors worldwide. In keeping with the site’s principles of open access and public control, all of its data are freely downloadable in various formats from the Planet.osm wiki page (http://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Planet.osm). Because it is a volunteer effort, the data isn’t always top-notch for reliability where there aren’t a lot of contributors. In the U.S., it primarily relies on U.S. Census roadway data, which has a lot of accuracy issues. The server dynamically renders tiles from vectors stored in a PostGIS database, resulting in the tiles being slower to load than cached map services like Google. The standard styling is smooth and colorful, and it can be restyled using one of the JavaScript libraries that support it, which are several. The most popular are OpenLayers, Leaflet, and the Google Maps API. Leaflet is a product of CloudMade, a company founded by Coast with the express purpose of serving OSM data to other websites and applications.

OSM home page, with OSM basemap and OpenLayers interface

OSM home page, with OSM basemap and OpenLayers interface

4. CloudMade: The company was founded by OSM founder Steve Coast with the express purpose of developing APIs and applications serving OSM data. They offer location-based services and a map style editor, a web application for styling OSM data and rendering the styled basemap. There are hundreds of user-styled basemaps already stored and publicly available on CloudMade’s server, which can easily be applied in OpenLayers or Leaflet. The latter is a JavaScript library they developed that has gotten rave reviews (For more on Leaflet, see Part 4).

One of CloudMade’s basemaps with a Leaflet interface

One of CloudMade’s basemaps with a Leaflet interface

5. ArcGIS Online: ESRI provides a wide variety of web development tools available to the public, which include a wealth of tiled basemaps and some spatial analysis functionality. They continue to get most of the federal government’s business for housing data and making it publicly available, and for good reason, as they have by far the most well-developed programming infrastructure and support for GIS applications. ArcGIS Explorer Online is a good tool for beginners who have a dataset or two lying around and just want to say, “look Ma, I made a web map!” (see Technology Research Memo #2). ESRI’s map server hosts quite a few basemap layers from a variety of government and NGO sources, as well as The National Map’s data layers through REST services. Basemaps include ocean relief, world physical (from the National Park Service), National Geographic world, National Geographic TOPO! (all USGS topographic quads), world imagery, world shaded relief, world streets (which uses NAVTEQ andTomTom street data), world terrain, and world topo. Folders on the server hold other thematic layers. Of the base maps, my favorite cartographically is the National Geographic style, with its classic earth tones, dignified label fonts, and present-but-not-overwhelming shaded relief. ESRI’s “World Topo” basemap is similar in content but with a lighter color scheme and more contemporary lettering. The ArcGIS Online interface has Bing-style smooth zooming and shift-zoom, but the jumps between scales are a bit too large in my opinion. Perhaps this is owing to being built on Microsoft development architecture. ESRI offers its API for JavaScript, Flex, and Silverlight, and non-commercial web use is free. The documentation is superb.

ESRI’s World Streets basemap and interface

ESRI’s World Topo basemap and interface

ESRI’s National Geographic basemap and interface

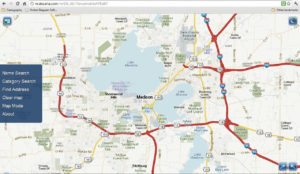

6. MapQuest: Way back in 1996, when “internet” was just starting to become a household word, MapQuest started out as the first online address matching and routing service with a map interface.4Though since overtaken by the big search engines, they’re still trying to lead the pack in developing new ways to be lazy and let your computer think for you, most recently by leaving your neighborhood streets out of their directions and telling you how much you’re going to pay for gas to get where you’re going. I still think MQ’s drive time estimates are more accurate than Google’s. In a car-oriented map, they could have left off the shaded relief when they redesigned around tiles, but the soft color scheme is appealing. Zoom has an even harder edge than Google’s. The standard basemap data comes from NAVTEQ, Intermap, and i-cubed for satellite imagery, but their APIs also support OSM data. MQ hosts APIs for JavaScript, Flash/Flex, and iOS, and for incentives they’re touting higher free usage limits and looser development rules than Google.

Mapquest’s basemap and interface

7. Nokia Maps: Formerly known as Ovi Maps, Finnish phone maker Nokia’s maps were built to run on its mobile devices. Nokia offers its own JavaScript Framework for Mobile HTML5 to create location-based mobile apps, as well as a web maps API and parameters for REST requests. As you might expect from a mobile device company, the map interface is straightforward and ultra-modern-looking, and location-aware on any GPS-enabled device. If you like your highways purple, their roadmap is for you. Zooming is fast, but with a slow enough connection you can catch a glimpse of the classy wallpaper they build their tiles on. With a hefty browser plug-in on full-size computers and high-end mobile phones, it can run in 3D mode, rendering buildings similarly to Google Earth (although presently inferior to Google’s 3D data).

Nokia’s basemap and desktop interface

8. Stamen: Ironically, the vast majority of people who have figured out the whole web mapping thing are computer scientists who happen to like maps, making a lot of cartographers feel like the guy who was popular in high school only to get sidelined as an adult by the once-antisocial nerd. Stamen Design gets the distinction of being a company of cartographers looking to reclaim innovator status in a Web 2.0 world. So far they have developed three unique and beautiful basemaps: artsy “Watercolor,” realist “Terrain,” and minimalist “Toner.” Each one leverages OSM data, and can be embedded using ModestMaps, Leaflet, OpenLayers, or Google Maps API. Stamen’s side project, PrettyMaps, layers data from three sources (OSM, Natural Earth, and Flickr) with transparent pastel styling to create a visually striking and geographically fascinating map image. It’s slow to load, but intentionally designed “for people who want to look under the hood and see the potential that these tools offer for making new and interesting maps.”8

Stamen’s example page with their Watercolor, Terrain, and Toner basemaps and a Modest Maps/Wax interface

9. Mapbox: An attempt at an all-in-one web map creation, hosting, and publishing platform built on open-source technology, the Mapbox project was begat by a consulting firm, Development Seed, whose primary business is mapping for international NGOs. The integrated suite of Mapbox software includes TileMill for loading vector data and creating custom tile layers, a cloud-based development application functionally similar to ArcGIS Explorer Online, a lightweight API for accessing the tiles on their server, and the JavaScript library Wax for integrating with other services such as Leaflet and Google Maps API. Tilemill and the mapmaker app have good step-by-step tutorials, but the limited API documentation may take some motivation and prior knowledge to get a handle on. The Mapbox basemap, Streets, renders OSM data with cartography that’s crisp and smooth; the white roads have the elegance of spiderweb strands. There are no imagery or terrain layers, but with the tools you need to access Mapbox Streets, you can easily get those layers from other sources.

MapBox example page with their Streets basemap in a Modest Maps/Wax interface

10. deCarta: This company’s main business is in providing location-based services (LBS), which entails their primary access points being GPS-enabled mobile devices. Their applications provide location-based searching and voice navigation on devices like iPhone and Android, and they also provide a Maps API (in JavaScript, Android, iOS, Samsung bata, and J2ME) geared toward businesses that want to put their locations on a web map, to which they allow limited free access. As you might expect with an interface designed for mobile, the zoom buttons are big and cliparty and the menu is a slide-out feature. The cartography looks like Google only more cartoonish.

deCarta’s basemap and interface

11. Yahoo! Maps (depricated): Worth mentioning only because they were once one of the Big 3 search engines with a map service. After forming a partnership with Nokia, in 2011 they completely deprecated their maps API. If you’re thinking about making a mash-up with Yahoo! Maps… don’t.

12. MSR Maps (depricated): Shut down on May 1, 2012, the service once known as Microsoft Terraserver came online in 1998 and was the first internet repository of viewable aerial imagery and USGS topographic quadrangles at multiple scales. Though since outpaced in interface features and image quality (it served black and white photos taken from aircraft), MSR Maps was still my favorite for quick access to USGS topo quad data. It had a limited API designed to provide access from .NET applications. The only other tile service like this at present is the National Geographic TOPO! basemap through ESRI’s map server (see #4), although contours are also available in Google’s Terrain basemap, and both traditional USGS quads and updated US Topo orthophoto quads are available to download as GeoPDFs from the USGS map locator website or The National Map.

13. Minor players: There are a few tile services that I elected not to cover in depth here because although they provide coverage of the U.S., they were developed more for other parts of the world and don’t provide anything new or unique. Two European ones are ViaMichelin—the quality of which befits a tire manufacturer—and France-based Mappy. An interesting Australia-based service is Nearmap, which provides satellite imagery—high-resolution for Australian cities, low-res NASA data everywhere else—from multiple timestamps. Their worldwide coverage only consists of monthly images from 2004, however. No doubt, by the time you read this, someone else will have thought of some new service to provide, and the world of web mapping will be even more confusing than it is now.

Reference:

42012. Web Mapping. Wikipedia. Accessed June 25, 2012. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_cartography

5Gosnell, D. M. 2005. Professional Development with Web APIs. Wrox Press.

62012. List of online map services. Wikipedia. Accessed June 21, 2012. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_online_map_services>

72012. OpenStreetMap. Wikipedia. Accessed June 25, 2012. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Openstreetmap>

82010. About Prettymaps. Stamen Design. <http://prettymaps.stamen.com/201008/about/>